I was unaware that cytomegalovirus (CMV) was an occupational risk for daycare educators when I became a licensed home daycare provider in Maryland in 1987. I was unaware that every year, 8 -20% of caregivers/teachers contract CMV.

My daughter Elizabeth was born severely disabled by congenital CMV in 1989. While I was pregnant with Elizabeth, I not only operated a licensed home childcare center, but I also volunteered in our church nursery with young children and was the mother of a toddler—all things that put me at higher risk for contracting CMV.

Elizabeth was due to be born on Christmas Eve, making my pregnancy with her an especially happy experience. But when she arrived on December 18th, I felt a stab of fear. My immediate thought was, “Her head looks so small—so deformed.” After a CAT scan, the neonatologist said, "Your daughter has microcephaly—her brain is very small with calcium deposits throughout. If she lives, she will never roll over, sit up, or feed herself." Further tests revealed Elizabeth's birth defects were caused by congenital CMV.

I was then given information that sent my head spinning—literally. I could barely see straight reading material from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) which stated, "People who care for or work closely with young children may be at greater risk of CMV infection than other people because CMV infection is common among young children..." I was stunned. How could it be that no one in the medical or childcare field thought to warn me of this? Nowhere in my childcare licensing training or church nursery training was CMV mentioned. CMV prevention was not discussed in my prenatal doctor visits.

I felt sick at what my lack of knowledge had done to my little girl. In milder cases, children with congenital CMV may lose hearing or struggle with learning disabilities. But Elizabeth's case was not a mild one. When my husband Jim heard Elizabeth's grim prognosis, he stared at her and said, “She needs me”—just like Charlie Brown with that pathetic Christmas tree.

It took me about a year, but I eventually stopped praying a nuclear bomb would drop on my house so I could escape my overwhelming grief over Elizabeth's condition. Life did become good again—but it took a lot of help from family, friends, some Valium, and the Book of Psalms. Although Elizabeth was profoundly mentally impaired, legally blind, had cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and a progressive hearing loss, we were eventually able to move forward as a happy, "normal" family.

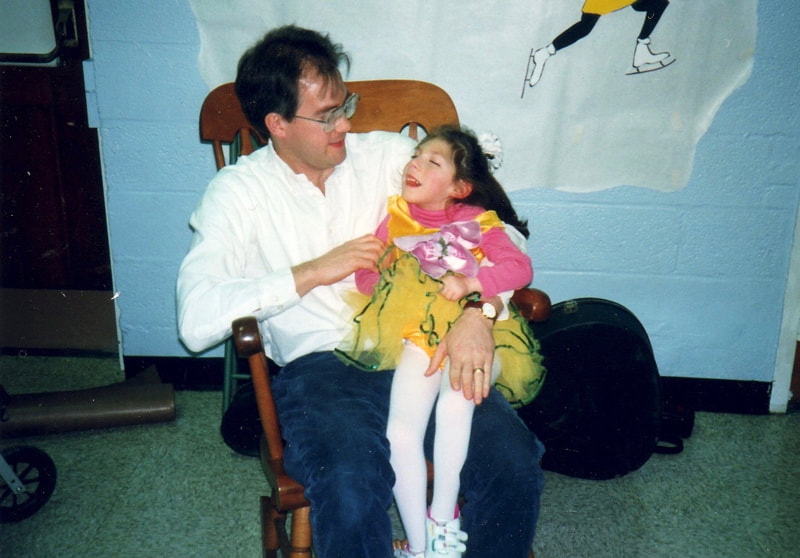

Years later, I awoke feeling so proud of Elizabeth. It was her 16th birthday and just one week before her 17th Christmas. When the song “I’ll be home for Christmas” played on the radio, I cried thinking how hard Elizabeth fought to be home with us, overcoming several battles with pneumonia, major surgeries, and seizures. Weighing only 50 pounds, she looked funny to strangers because of her small head and adult teeth, but she was lovely to us with her long brown hair, large blue eyes and a soul-capturing smile. She even won the "Best Smiling Award" at school. Although still in diapers and unable to speak or hold up her head, Elizabeth loved sitting on the couch with her fat, old dog and going for long car rides. She especially enjoyed school and being surrounded by people, paying no mind to the stares of “normal” children who thought she belonged on the "Island of Misfit Toys."

In 2006, less than two months after she turned 16, I dropped Elizabeth off at school. Strapping her into her wheelchair, I held her face in my hands, kissed her cheek, and said, “Now be a good girl today.” She smiled as she heard her teacher say what she said every time, “Elizabeth is always a good girl!” With that, I left.

At the end of the day, I got the call I always feared. “Mrs. Saunders, Elizabeth had a seizure and she’s not breathing." The medical team did all they could, but she was gone. While holding Elizabeth’s body on his lap, my husband looked down into her partially open, lifeless eyes and cried, “No one is ever going to look at me again the way she did.”

Shortly after Elizabeth died, I had a nightmare: visiting a support group of new parents of children with congenital CMV, they suddenly looked at me and asked, “Why didn’t you do more to warn us about CMV?” When I awoke in a cold sweat, I knew I had to make CMV awareness my life’s work.

Many women have joined me or advised me in my work to educate women on how to protect their pregnancies. Marti Perhach, GBSI's cofounder and whose daughter Rose was stillborn due to group B strep, was the first. One friend, former lead singer for Rolling Stone Magazine’s house band, Debra Lynn Alt, wrote and recorded a song about a mother wishing someone had told her how to protect her pregnancy. Click on "Had I Known," music and lyrics by Debra Lynn Alt, to hear a mother's wish.

You can watch Elizabeth grow up and learn CMV prevention in this short music video about a child who couldn't speak, and learn more about my CMV books, articles and resources on my blog at: https://congenitalcmv.blogspot.com

Sincerely,

Lisa Saunders

Child Care Providers Education Committee

National CMV Foundation

[email protected]

Update as of December 27, 2022: How a Baldwinsville mother fought for 30 years to pass a law that might have saved her daughter

My daughter Elizabeth was born severely disabled by congenital CMV in 1989. While I was pregnant with Elizabeth, I not only operated a licensed home childcare center, but I also volunteered in our church nursery with young children and was the mother of a toddler—all things that put me at higher risk for contracting CMV.

Elizabeth was due to be born on Christmas Eve, making my pregnancy with her an especially happy experience. But when she arrived on December 18th, I felt a stab of fear. My immediate thought was, “Her head looks so small—so deformed.” After a CAT scan, the neonatologist said, "Your daughter has microcephaly—her brain is very small with calcium deposits throughout. If she lives, she will never roll over, sit up, or feed herself." Further tests revealed Elizabeth's birth defects were caused by congenital CMV.

I was then given information that sent my head spinning—literally. I could barely see straight reading material from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) which stated, "People who care for or work closely with young children may be at greater risk of CMV infection than other people because CMV infection is common among young children..." I was stunned. How could it be that no one in the medical or childcare field thought to warn me of this? Nowhere in my childcare licensing training or church nursery training was CMV mentioned. CMV prevention was not discussed in my prenatal doctor visits.

I felt sick at what my lack of knowledge had done to my little girl. In milder cases, children with congenital CMV may lose hearing or struggle with learning disabilities. But Elizabeth's case was not a mild one. When my husband Jim heard Elizabeth's grim prognosis, he stared at her and said, “She needs me”—just like Charlie Brown with that pathetic Christmas tree.

It took me about a year, but I eventually stopped praying a nuclear bomb would drop on my house so I could escape my overwhelming grief over Elizabeth's condition. Life did become good again—but it took a lot of help from family, friends, some Valium, and the Book of Psalms. Although Elizabeth was profoundly mentally impaired, legally blind, had cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and a progressive hearing loss, we were eventually able to move forward as a happy, "normal" family.

Years later, I awoke feeling so proud of Elizabeth. It was her 16th birthday and just one week before her 17th Christmas. When the song “I’ll be home for Christmas” played on the radio, I cried thinking how hard Elizabeth fought to be home with us, overcoming several battles with pneumonia, major surgeries, and seizures. Weighing only 50 pounds, she looked funny to strangers because of her small head and adult teeth, but she was lovely to us with her long brown hair, large blue eyes and a soul-capturing smile. She even won the "Best Smiling Award" at school. Although still in diapers and unable to speak or hold up her head, Elizabeth loved sitting on the couch with her fat, old dog and going for long car rides. She especially enjoyed school and being surrounded by people, paying no mind to the stares of “normal” children who thought she belonged on the "Island of Misfit Toys."

In 2006, less than two months after she turned 16, I dropped Elizabeth off at school. Strapping her into her wheelchair, I held her face in my hands, kissed her cheek, and said, “Now be a good girl today.” She smiled as she heard her teacher say what she said every time, “Elizabeth is always a good girl!” With that, I left.

At the end of the day, I got the call I always feared. “Mrs. Saunders, Elizabeth had a seizure and she’s not breathing." The medical team did all they could, but she was gone. While holding Elizabeth’s body on his lap, my husband looked down into her partially open, lifeless eyes and cried, “No one is ever going to look at me again the way she did.”

Shortly after Elizabeth died, I had a nightmare: visiting a support group of new parents of children with congenital CMV, they suddenly looked at me and asked, “Why didn’t you do more to warn us about CMV?” When I awoke in a cold sweat, I knew I had to make CMV awareness my life’s work.

Many women have joined me or advised me in my work to educate women on how to protect their pregnancies. Marti Perhach, GBSI's cofounder and whose daughter Rose was stillborn due to group B strep, was the first. One friend, former lead singer for Rolling Stone Magazine’s house band, Debra Lynn Alt, wrote and recorded a song about a mother wishing someone had told her how to protect her pregnancy. Click on "Had I Known," music and lyrics by Debra Lynn Alt, to hear a mother's wish.

You can watch Elizabeth grow up and learn CMV prevention in this short music video about a child who couldn't speak, and learn more about my CMV books, articles and resources on my blog at: https://congenitalcmv.blogspot.com

Sincerely,

Lisa Saunders

Child Care Providers Education Committee

National CMV Foundation

[email protected]

Update as of December 27, 2022: How a Baldwinsville mother fought for 30 years to pass a law that might have saved her daughter